The Competition Authority is developing measures to eliminate discriminatory or otherwise unfair treatment in the rail services market. It is also one of the important tasks of the Competition Authority to deal with complaints made by railway undertakings. If a railway undertaking considers that it has been unfairly treated by the infrastructure manager when approving a railway network statement, allocating capacity, organising coordination proceedings, declaring a capacity exhausted, drawing up a traffic schedule, organising traffic management, planning upgrades, carrying out maintenance work, or setting a user fee, it may lodge a complaint with the Estonian Competition Authority.

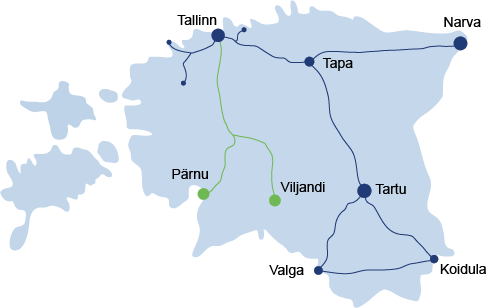

In Estonia, there are infrastructure managers, i.e. AS Eesti Raudtee and Edelaraudtee Infrastruktuuri AS, the railways managed by whom are designated for public use. AS Eesti Raudtee manages 1,229 km of railways and provides the service of giving railway infrastructure into use to railway undertakings and rolling stock owners, together with traffic management. Edelaraudtee AS manages 222.1 km of railways, providing similar services.

AS Eesti Raudtee is marked with blue and Edelaraudtee Infrastruktuuri AS with green on the figure.

The competent authority for passenger transport organised in railway traffic is the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications and for the transport of passengers within a rural municipality or city, a local government may also be involved. Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications has entered into a public service framework agreement for the years of 2018–2022 with AS Eesti Liinirongid (according to the company’s trademark Elron) to the extent of the entire volume of public passenger transport in Estonia. On the international passenger train line Tallinn–St.Petersburg–Moscow, AS GoRail carried out passenger transport; the company also sells tickets for all passenger trains to the Baltic States, the CIS countries and the countries in connection with them, including onward journeys between Finland and Russia.

As of 2020, 14 undertakings held operating licences for rail transport of goods, but the majority of them were restricted to non-public railways, i.e. local transport of goods (e.g. ports and mines). The largest company operating on public railways was AS Operail.

According to Statistics Estonia, in 2020 almost 6 million passengers travelled by train, which is 29% less than a year earlier. There were 15.8 million tonnes of goods on railways with freight transport decreasing by 26% compared to 2019. The coronavirus strongly affected the transport of rail passengers both at the beginning of last year and during the second wave at the end of the year, and the volume of freight transported by rail also decreased to an important extent. At the end of the year, however, there was some recovery in volume. Rail passenger turnover fell by 33% to 263 million passenger-kilometres (passenger turnover shows how many passengers and how far they were transported by rail and is expressed in passenger-kilometres, where one passenger-kilometre means one passenger-kilometre).

The highest number of passengers was travelling by rail in the first quarter, when the figure was only 8% lower than in the previous year. In the second quarter, however, the number of passengers was less than one million, or half as much as in 2019. In the third quarter, a fifth fewer people travelled by train, and in the fourth quarter, almost a third less than a year earlier. The main decrease in freight transport by rail was in domestic transport, which decreased by almost half. The freight turnover of rail transport decreased to 1.7 billion tonne-kilometres. Freight turnover includes the quantity of goods transported and the distance travelled and is measured in tonne-kilometres (one tonne-kilometre means the transport of one tonne of goods over one kilometre). In the first half of the year, goods were transported in a volume of more than a third less than in the same period of the previous year, in the second half by 13% less. The volume of freight on the public railway decreased by 15% to 11.3 million tonnes, the freight turnover by 18% to 1.5 billion tonne-kilometres.

In October 2020, a new version of the Railways Act entered into force, which was due to the need to transpose the directives of the European Parliament and the Council on the interoperability of the railway system and railway safety into Estonian law. However, as the Railways Act adopted in 2003 has been extensively and repeatedly amended (more than 30 times) since its adoption, this had made the text difficult to read at times, containing numerous superscripts and paragraphs that had a length of several pages, drafting the new redaction ensured a better readability and logical structure of the text of the law. Compared to the amendments to the Railways Act adopted in 2018, which supplemented the tasks of opening up the market for domestic rail passenger services and managing railway infrastructure, and further clarified the requirements to ensure independence of railway undertakings and non-discriminatory treatment of capacity applicants and effective competition, the entry into force of the new wording of the text did not add any additional tasks to the Competition Authority.

In December 2020, the National Audit Office published an overview of the aims for the development of the Estonian railway sector and how these goals have been implemented in the last ten years (2010–2019) and how they are planned to be implemented in the future. It was examined whether the state has a vision of the role that Estonian rail will play in the movement of passengers and goods in the future, how the set aims will be achieved and how much it could cost.

In summary, the National Audit Office found that the state does not have a comprehensive plan for the development of the railway: various strategy documents set out a number of objectives that are to be achieved in the railway sector, but there is no unified plan for their implementation. It would be sensible to develop railways in coordination with other modes of transport in order to better organise the movement of both goods and passengers.

The maintenance and development of railway infrastructure is financed from railway infrastructure charges set by the Consumer Protection and Technical Regulatory Authority (TTJA). Railway infrastructure charges consist of a fee for the use of basic services, i.e. a minimum access package fee to be paid by all carriers, based on the rate set by the TTJA, calculated on the basis of the methodology set out in European Union legislation. If the TTJA assesses solvency as low, infrastructure managers will receive less railway infrastructure charges for the maintenance of the railway and the state will have to pay the unpaid part from its budget. If TTJA assesses the solvency of the sector as high, there is a risk that freight transport by rail will decrease further and railway infrastructure charges for freight will still be lost. In the two years shortcomings have also been revealed in the new methodology for railway infrastructure charges, for which TTJA is looking for solutions, clearer targets could still be set at the national level for the amount and nature of additional charges for the basic railway infrastructure charge. This means that the state should decide what is the objective it wants to achieve with the implementation of the additional charges – whether to create a competitive advantage for rail freight, to maximize the revenue from freight carriers or something else entirely.

The Authority has also drawn attention to the issue of railway infrastructure charges in the analysis published in March 2020.